Fed has fallen behind the inflation curve

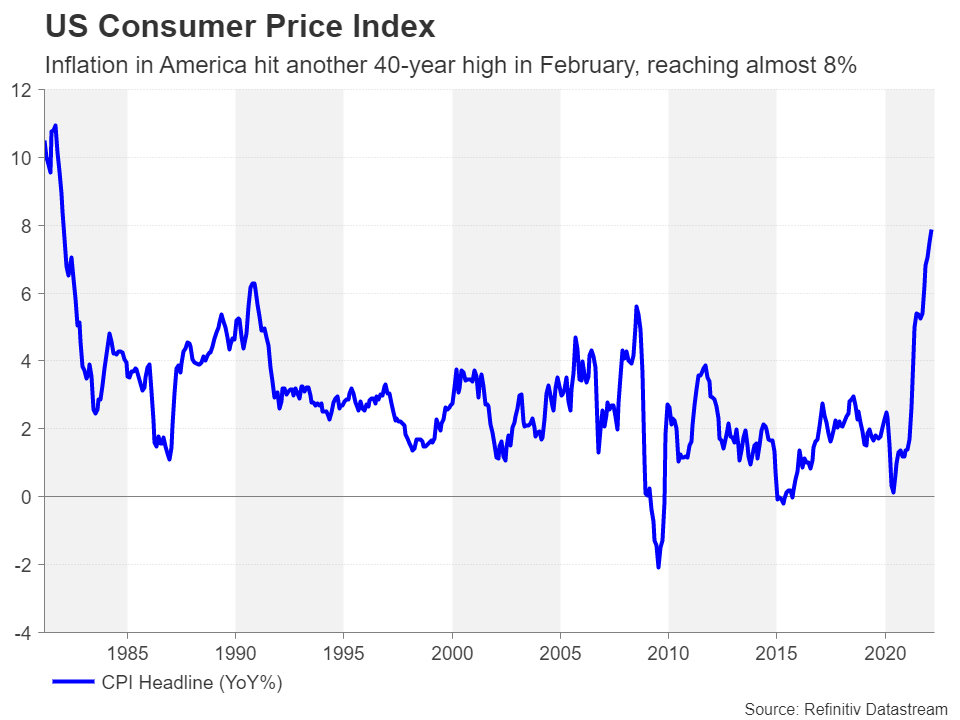

Before the pandemic, the days of high inflation were considered to be a thing of the past. But the virus crisis and ensuing lockdowns changed all that. If crippled supply chains and component shortages weren’t enough, the global economy now also has to grapple with soaring commodity prices as Western sanctions against Russia have roiled the commodities market.

In America, where the powerful stimulus both by Congress and the Fed boosted pent-up demand more than in any other country, headline inflation surged to 7.9% y/y in February – the highest in 40 years. Under normal circumstances, interest rates would already be well on their way up by now, but the pandemic-induced economic shock has had policymakers walking a very thin line.

Trying not to scare the markets

However, with the war in Ukraine compounding price pressures, the Fed isn’t in a position to stay in the slow lane much longer and needs to get a grip on inflation, or at the very least, be seen to be doing so. So far, the Fed has tried to avoid making too many U-turns as its narrative of ‘transitory inflation’ crumbled, and thus, Powell has been reluctant to join some of his more hawkish colleagues in calling for a 50-bps rate rise.

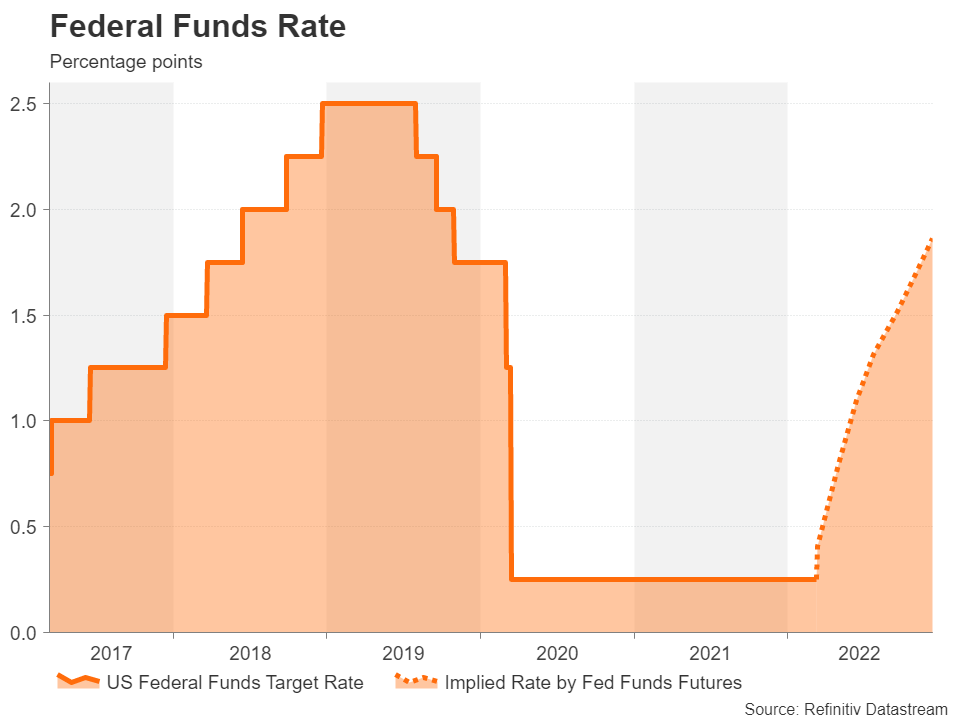

But the preference for a gentle liftoff hasn’t prevented speculation about subsequent rate increases from going into overdrive. Fed fund futures are currently implying almost seven 25-bps rate hikes this year, up from six and a half right before the Ukraine crisis erupted and from five and a half in the immediate aftermath.

The dreaded dot plot and the dollar

The updated dot plot containing the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) latest projections will likely determine whether those bets are scaled down or up. If the median projection is for six rate hikes, investors will probably perceive that to be quite hawkish, bolstering the dollar, particularly against the yen.

However, if FOMC members take a more cautious stance and signal less than six rate rises, the dollar could ease slightly. Policymakers have been keen to stress lately that they are more data-dependent than ever due to the huge uncertainties surrounding their inflation forecasts as well as how the Ukraine conflict will unfold so they may not want to ‘overcommit’.

Shrinking the balance sheet

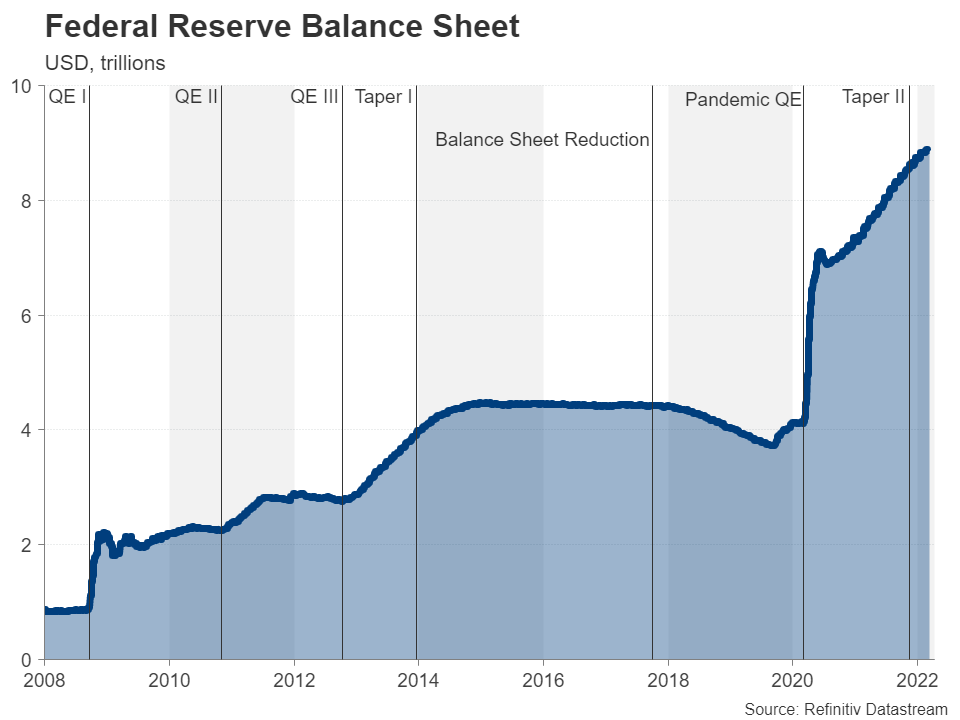

Another risk factor from the Fed meeting is the long-awaited decision on the balance sheet. Powell indicated in his recent hearing before congressional lawmakers that the Fed will outline at its March meeting how it intends to wind down its massive balance sheet of nearly $9 trillion.

At this point, the Fed will probably simply begin the process of letting its holdings roll off when they mature rather than reinvest in them. However, Powell will likely be asked in his press briefing whether there are any plans to actively start selling Treasuries and mortgage securities. If he hints that such a decision is possible in the not-too distant future, bonds could take a hit, sending yields higher and stocks lower. A faster-than-expected pace of balance sheet runoff could spark a similar reaction.

However, for the dollar, the impact from the balance sheet reduction might not be as obvious straight away, especially when geopolitical tensions remain so elevated. Still, any surprises from this front would certainly add to the volatility.